Space in the Run series is kind of complicated, all because of a decision I made early on. See, I had a problem: how can I program a game where you run on the walls and ceiling? I’d made platformers before, but never anything where “up” could become “left” at a moment’s notice.

My answer was abstraction. I would program the physics exactly the way I was used to. The Runner would move around in her own little world where “up” means up and “down” means down. This meant I could focus on getting the running and jumping physics to feel just right. Then after those physics had run, I would use a mathematical formula to rotate everything by some multiple of 90°, depending on which wall the Runner was really on.

Well, kind of. The actual details varied from game to game, but the core guiding principle remained “I want the jump physics to be easy to program.” In Run 1 I took several shortcuts. By the time I got to Run 3 and Runaway, I was using 3D matrices to accurately convert between nested coordinate spaces.

Coordinate spaces

Cartesian coordinate systems use numbers to represent points. Coordinate spaces are when you’re using a coordinate system to represent physical space. They can be two dimensional, three dimensional, and even more. (Though I’m going to focus on 3D for obvious reasons.)

Those right there are coordinate spaces. Both are defined by their origin (the center point) and the axes that pass through that origin. As the name implies, the origin acts as the starting point; everything in the space is relative to the origin. Then the axes determine distance and direction. By measuring along each axis in turn, you can place a point in space. For instance, (2, 3) means “2 units in the X direction and 3 units in the Y direction,” which is enough to precisely locate the green point.

Axis conventions

Oh right, each axis has a direction. The arrow on the axis points towards the positive numbers, and the other half of the axis is negative numbers. I like to use terms like “positive X” (or +X) and “negative Y” (or -Y) as shorthand for these directions.

By convention, the X axis goes left-to-right. In other words, -X is left, and +X is right.

The Y axis goes bottom-to-top in 2D, except that computer screens start in the top-left, so in computer graphics the Y axis goes top-to-bottom. I would guess that this stems from the old days when computers only displayed text. In English and similar languages, text starts in the top-left and goes down. The first line of text is above the second, and so on. It just made sense to keep that convention when they started doing fancier graphics.

In 3D, the Z axis is usually the one going bottom-to-top, while the Y axis goes “forwards,” or into the screen. Personally, I don’t like this convention. We have a perfectly good vertical axis; why change it all of a sudden?

In Runaway, I’ve chosen to stick with the convention established by 2D text and graphics. The X axis goes left-to-right, the Y axis goes top-to-bottom, and the Z axis goes forwards/into the screen. If I ever use Runaway for a 2D game, I want “left,” “right,” “up,” and “down” to mean the same things.

Not that it matters much. Runaway doesn’t actually enforce +Y meaning “down.” I wrote comments suggesting that it should, but because of the nature of the games I was building, I never hard-coded it. Instead, I coded ways to define your own custom coordinate spaces.

Rotated coordinate spaces

You know how different game engines can assign different meanings to different axes? Well in fact, each individual coordinate space can assign different meanings to different axes. In a single game, you can have one coordinate space where +Y means “down,” another where it means “up,” and a third where it means “forwards.”

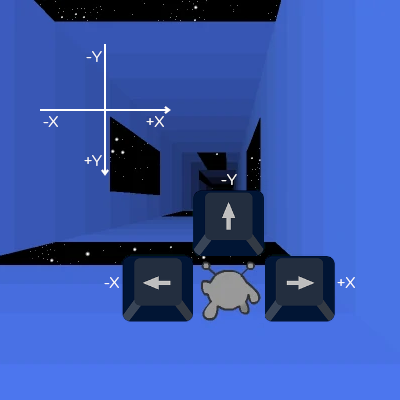

This brings us back to Run. I wanted to program character motion in a single, consistent coordinate space. I wanted to be able to say “the left arrow key means move in the -X direction, and the right arrow key means move in the +X direction,” and be done with it. Time for a couple images to show what I mean.

Above is the basic case. You’re on the floor, and the arrow keys move you left, right, and up. If the game was this simple, I wouldn’t have anything to worry about.

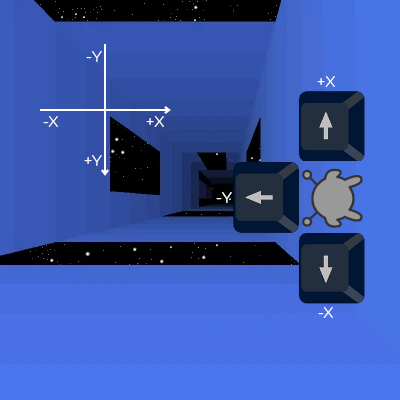

Once you touch a wall, the Runner’s frame of reference rotates. She now has a distinct coordinate space, rotated 90° from our perspective. She can move around this space just like before: left arrow key is -X, right arrow key is +X, and jump key is -Y. It works great, until she has to interact with the level.

In her own coordinate space, she’s at around (-1, 2, 5). (Assuming 1 unit ≈ 1 tile.) In other words, she’s a bit left of center (X = -1) on the floor (Y = 2) of the tunnel. But wait a minute! In the tunnel’s coordinate space, the floor has a wide gap coming up quick. If the Runner continues like this, she’ll fall through! That can’t be right.

To fix this, we need to convert between the two coordinate spaces. We need to rotate the Runner’s coordinates 90° so that they match the tunnel’s coordinates, and then check what tiles she’s standing on. We end up with (2, 1, 5) – a bit below center (Y = 1) on the right wall (X = 2) of the tunnel. That wall doesn’t have a gap coming up, so she won’t have to jump just yet. Much better.

I have other use cases to get into, one of which is something I’m still working on and prompted this blog post. But I’ve spent long enough on this post, and I really should get back to the code. Perhaps next week.

I want to play run 3

then go to https://player03.com/run/3/beta/