Lately, I’ve been thinking: I find a lot of cool media online, and almost never share or promote it even though I have a platform. So let’s fix that!

Each post in this series will start with a quick summary to convince you to go look at the thing for yourself, and then I’ll dive in and overanalyze it. (Don’t worry, spoilers will be marked ahead of time.)

Space Station Weird

Space Station Weird is Luke Humphris’s big project over the past year. Set at some nebulous point in the future, it stars a “fridge dude” tasked with maintaining a seemingly-empty space station.

At the time of this writing, there are three episodes, totaling about seven minutes long. Check them out!

Space Station Weird doesn’t have intense action or laugh-out-loud punchlines. Instead, it thrives on mystery, worldbuilding, and understatement. And there’s a quiet sort of humor in the way the narrator sounds so bored as he describes such weird concepts.

I also like the fact that it’s done by one single person. It feels like something I theoretically could make, if I spent enough time practicing that art style, not to mention sound design, animating, and voice acting. The fact that it’s (almost) within the realm of my abilities makes it more impressive to me, since I can tell how it was done and how much effort that would take.

Whereas in the case of [insert big-budget movie/game], everything is polished so well that I can’t tell how they did it or how much effort it took per person, which makes it feel less impressive. Is that just me?

Analysis

Now that you’ve had a chance to see it for yourself, here are some of my ideas about the story. Light spoilers ahead, but I’ll avoid specifics.

Horror?

With only a few small tweaks, this could be a horror story. Being stranded alone in deep space is the perfect opportunity for horror. (We know this because it’s been done so many times.)

But in this case, we get this totally blasé fridge dude, who spends more time commenting on the station’s architecture than he does on genuinely worrying information. That isn’t to say he’s ignorant of danger, he’s just very calm about it. (With one exception so far.) And since the narrator is calm, the viewer gets to be calm too. Considering the title, that’s clearly intended: we aren’t watching “Space Station Existential Dread,” we aren’t watching “Space Station Eldritch Abominations from Beyond the Cosmos,” we’re just watching “Space Station Weird.”

It certainly could become a full-on horror story in the future, but I doubt it. I think it’s good at being a sci-fi slice of life, and will continue in that vein.

Speaking of which, sci-fi isn’t specifically about the future, or outer space; it’s about possibility. Sci-fi asks, what could happen if X was true? X can be “it’s the future in space with fancy gadgets,” but that isn’t necessary. And if that’s the only change, you get a relatively boring story.

On the other hand, Frankenstein is often described as a foundational work of science fiction despite being set on Earth in the modern day. It only had one major difference: scientists could (re)create life. (And promptly neglected and shunned said newly-created life.) Exploring this possibility is what makes it sci-fi, at least according to this one definition.

And I think Space Station Weird will fall under this definition too. It won’t be a story about Fridge Dude escaping alive (horror), or killing aliens in self-defense (action), but rather learning to coexist with whatever lurks here. You know, before it kills him. That’s totally different.

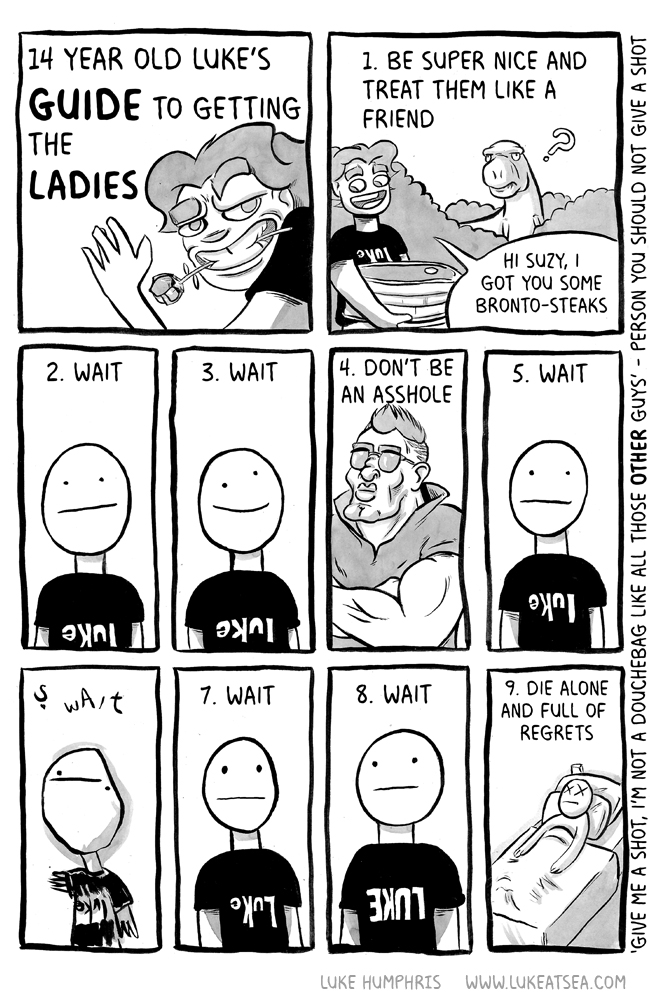

Luke Humphris’s prior works

Space Station Weird is still quite short, but it follows up on several concepts from Luke’s prior work, so let’s take a moment to look at that and see what we can learn. Or skip ahead to the next section, I can’t stop you.

My first exposure to Luke Humphris was while he was writing Dumb Drunk Australian, a long-form autobiographical webcomic. I stumbled upon it towards the end, but upon re-reading, it gets really dark at times. You’ve been warned.

Stories talking about my experiences with Australian drinking culture and toxic masculinity as well as feelings of not belonging.

TW: alcohol, suicide

–Description from the comic’s Gumroad page

I think the comic caught my attention because I liked seeing him explain things with silly faces.

The things being explained weren’t always fun…

…But Luke knows how to turn bad times into good anecdotes. Sometimes all it takes is a calm reaction to a bad situation, or a completely blank-faced reaction to a weird situation.

So yeah, his writing style and sense of humor were there all along.

Dumb Drunk Australian ends rather suddenly. Maybe some pages got lost, but it was going to have to end at some point. The comic was supposed to be about looking back with the benefit of hindsight, not chronicling his life in real time.

Instead, he made a new comic to chronicle his life in real time. My Body is a Bad Robot tells us about his daily life as he struggles to quit drinking. It’s… more positive on average than DDA, but still has some very dark moments.

On the other hand, it includes this extremely normal picture of him questioning his sexuality.

![I don't have to classify anything / I'm just very confused / Dropping expectations / Feeling like myself / Looking internally / [Luke is lying down with his mouth wide open; his eyes bulge out of his head and bend 180° down to look inside]](/wp-content/uploads/luke_internal.jpg)

I said earlier I don’t think Space Station Weird is going to turn into straight-up horror. A big part of that is because Luke spent so much time developing his offbeat, understated brand of humor, and I’m hoping he keeps playing to this strength.

Space and time

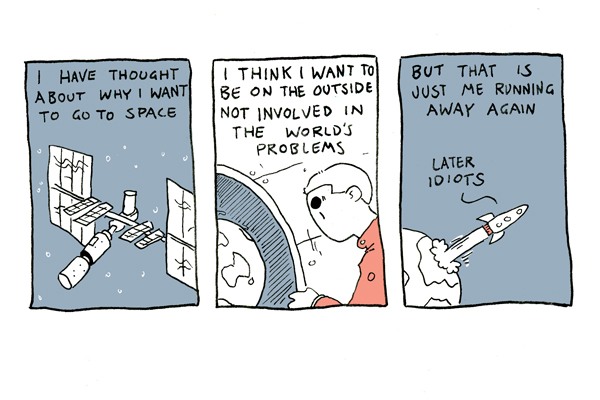

In Bad Robot, Luke occasionally mentions that he’s spent a lot of time thinking about space.

It’s rude to try to psychoanalyze an author you’ve never met, but what if they psychoanalyze themself and you quote them? Is it ok then? (I sure hope so!)

Running from problems is a recurring theme in Luke’s comics. In DDA, Luke literally runs away from a faceless character labeled “problems.” More than once. And in one of the two (I forget which), he briefly fantasizes about going into a coma until everything is better.

Is this what Space Station Weird is about? Is Fridge Dude running from problems, spending all his time asleep so he can skip ahead to some future utopia? Is he traveling to space just to be away from the world?

I don’t think so. It isn’t foreshadowed, nor does he mention it. Fridge Dude isn’t running from anything, he’s just already disconnected from reality. The world isn’t progressing towards utopia as far as he can tell (though he mentions that other fridge dudes think so). He didn’t even choose to go to space; a powerful corporation assigned him there.

If Luke’s writing process is anything like mine, I’d guess that these are all recycled ideas. For instance, after spending some time thinking about the coma concept, you might realize the problems with it. Whether or not the world got better, you’d be too alienated to tell. Not something worth putting yourself through, but potentially something worth putting a fictional character through.

Exploring the possibility further, you might start to flesh out the character’s personality: aloof, skilled but maybe not up-to-date, with hobbies that allow for long breaks. If you’re simultaneously developing an interest in space, it wouldn’t take long to realize ways that it complements the character: physical distance as a metaphor for emotional distance, plenty of machinery that needs to be repaired by someone who knows how old tech works.

A lot can go wrong on a space station (don’t tap the glass!), and you might write those down to use as plot points. Then perhaps you spend a day sketching fun zero-G room designs, and in the process you happen to think of a reason a space station might have been built with all these different styles. Suddenly you have a backstory for the station! By following ideas and seeing what their consequences might be, you can turn vague daydreams into a detailed setting and plot outline. (Now just add small details to finish up.)

I don’t know if this is really how it went down, but it could have been. At the very least, think of these last four paragraphs as a glimpse into my own writing process.

The weird messages

Unmarked spoiler warning from here on out. This is your last chance to watch the videos for yourself.

Episode 0 is mainly scene setting, which might be why it’s number 0. Episode 1 is the first time we get a good look at the station and start getting hints about the plot.

– The station is built in a ton of mismatched styles. At least one of these areas still uses an ancient Windows computer.

– Fridge Dude was woken up to work on life support systems, systems that wouldn’t be needed if he wasn’t awake.

– There’s no timeline for when he gets to go home.

– Fridge Dude’s bunk has a frankly ridiculous number of scary messages scrawled above it, plus a bloody handprint and what might be a claw mark. Or as Fridge Dude describes them, “a few weird messages.”

What do these clues point towards? Is it all one big mystery or multiple smaller ones?

I think the most straightforward explanation would be the horror one. There’s a monster on board, one that requires oxygen and occasionally eats people. Each previous group built a different section of the station in a different style, then scratched a message or two into the bunk before the monster killed them, leaving them unable to update their computer software. Fridge Dude is merely the latest sacrifice, and isn’t meant to make it home. Why? Who knows.

Possibly the weirdest explanation I can think of is that all the machines gained sentience somehow. Phil asked Fridge Dude to repair the oxygen machine for the oxygen machine’s benefit, not Fridge Dude’s. That could also explain what Phil means by “family” and “we love each other.” And why a spacesuit is walking around on its own. This doesn’t explain the weird messages, or why Fridge Dude was penalized for losing the suit, but perhaps there are multiple separate mysteries afoot.

Speaking of which, I suspect the weird messages might not be literal. As Monty Python points out, if someone was dying they wouldn’t bother to carve “aaarrgghh,” they’d just say it. Would a dozen different murder-victims-to-be all take the time to carve their last words into the same spot? Seems unlikely if you think about it. I’ve thought of one reasonable alternative so far: maybe someone carved the messages there as a trick. For whatever reason they wanted to make Fridge Dude think people died, and went overboard with the number of messages.

Conclusion and episode 3

A lot of mysteries remain in the weird world of Space Station Weird. Which is good, because IMO that’s one of its biggest appeals. That and the humor.

Exciting news: as of March 31, episode 3 has arrived on Patreon! Consider supporting Luke to see it now, though I’m sure it’ll come out on YouTube soon enough.

Episode 3 is what prompted me to finish writing this post, which I made sure to do before watching it, so I wouldn’t spoil anything that isn’t already public. But I can at least make predictions! If trends continue, this episode will contain one new non-human character, a small number of answers, a large number of questions, and at least one moment where Fridge Dude has a calm reaction to something ridiculous and/or terrifying. Oh, and Luke mentioned that he pushed his limits on some scenes, so expect cool visuals too.

When it comes out, I’ll try to resist the urge to come back here and delete/replace all my wrong guesses. But no promises!

![I genuinely believe that if you do not learn from your mistakes, they will come back worse and worse / Not in a karma type of way, but in a logical way / [Luke holds an near-empty glass; to his left are two already-finished glasses; to his right are two still-full glasses marked "poison"] / "Why does this keep happening?" / Being ignorant to what changes you need will only make a hard life](/wp-content/uploads/luke_mistakes.jpg)

![The place I lived in was near Windsor Castle / When I came home one night there were 2 guards drinking in the kitchen with some housemates / It was a fairly loud house / [Luke, appearing half asleep, stares blankly at the guards] / [Luke continues blankly staring as he begins to walk away] / [Luke continues blankly staring as he walks out of sight]](/wp-content/uploads/luke_guards.jpg)